Presentation at the International Vladimir Nabokov Symposium

St. Petersburg, July 15, 2002

Online version for the Vladimir Nabokov Museum

Nabokov’s Berlin

by Dieter E. Zimmer

IN 2001, a book of mine was published that dealt with the fifteen years Vladimir Nabokov spent in Berlin, from 1922 to 1937. It is mainly a picture album, based on a collection of photos on the subject. Years of part-time search had gone into this collection. It is a pity that for reasons of copyright, most of its photos, many of them brilliant, cannot be shown on the Internet. That is why here are just a few picture postcards that are in the public domain. This page thus does not represent the book nor its St. Petersburg presentation but is just a faint and fuzzy mirror reflection of both.

|

|

|

|

Police Headquarters near Alexanderplatz |

And of course his language students, among them possibly one Dietrich, the executions maniac. He thought Germany was the epitome of poshlost. He took little interest in German affairs as if they did not concern him, so little that he did not perceive the fundamental change that went on in the spring of 1933 in all its enormity and portent. So one might assume there never was what might be termed Nabokov’s Berlin. Yet there was.

Berlin and its townspeople were all around him, from morning to night he came across them in the streets and the shops, in the buses and streetcars, the parks and gardens, the cinemas, the libraries, the fun fair of Lunapark, the Sportpalast were he went for boxing and ice hockey matches, the soccer fields. He always was a most keen observer, and he needed an ample supply of everyday reality for his novels and stories. So he took it where he had occasion to observe it, and that was Berlin. Many stories and six of his early novels where fully set in Berlin and two partly. They are full of Berlin. It is true that it is not a Berliner’s Berlin the way it is in Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, for instance. It is mostly Russian Berlin, but it is Berlin all the same. Even ignoring much of Berlin seems a typical Berlin trait. Berlin is made up of many different milieus that hardly take any notice of each other. Not caring about other milieus than one’s own is a widespread and normal Berlin attitude up to this day.

It so happened that four bestselling German novels set in Berlin were written in the late 1920s, at the same time as Nabokov’s King, Queen, Knave the German translation of which was not a bestseller. They were Menschen im Hotel by Vicky Baum, Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin, Fabian by Erich Kästner and Bruder und Schwester by Leonhard Frank. There is much more of Berlin to be seen in King, Queen, Knave than in any of them. Döblin’s extraordinary novel has more of the city only insofar as it has its idiom and its way of thinking; in this sense it is a close-up while Nabokov’s fiction stays at a neutral distance. But Döblin’s city itself is reduced to a few blocks between Alexanderplatz and Rosenthaler Platz. Döblin lived not far away, and I believe Nabokov never ventured into those proletarian quarters. Nabokov's Berlin by contrast is the "Russian Berlin" of Wilmersdorf, Charlottenburg and Schöneberg, the city center and the city's parks and forests, notably the Grunewald.

|

|

|

Statue of Empress Auguste Viktoria in Tiergarten park |

|

|

|

Hercules on the Lichtenstein Bridge across the Landwehrkanal |

|

|

|

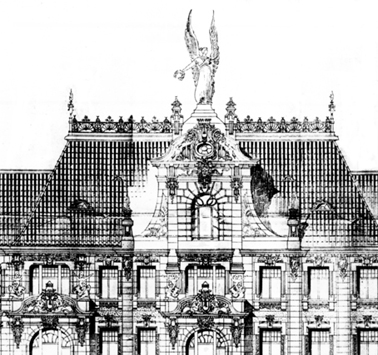

Ornamented apartment house on Kurfüstendamm |

|

|

|

The U-Bahn surfacing between Wittenbergplatz and Nollendorfplatz |

|

|

|

Barber shop at the department store KaDeWe, very untypical, but very close to the one in the story Razor |

It can safely be said that no other city is as tightly interwoven into Nabokov’s work as Berlin. There are hundreds of passages in his work dealing with some detail of the place. He had an uncanny eye for detail that nobody else seemed to take note of.

Did anybody else ever notice that the statue of Empress Auguste Viktoria in the Tiergarten held a sort of fan made of stone?

How many in the legions crossing that bridge across the Landwehrkanal have appreciated the muscleman was Hercules coping with the lion?

Who ever looked up to those banal stucco ornaments along the roofs (of Kurfürstendamm?) to see them transformed by the setting sun into “translucent porticoes, friezes and frescoes, trellises covered with orange roses, winged statues that lifted skyward golden, unbearably blazing lyres,” as they are in Details of a Sunset?

In his books there definitely is “Nabokov’s Berlin,” a city distinguished by his keen and personal way of looking at it.

I had easily recognized in his books the city of my early childhood. For instance, when I read Laughter in the Dark for the very first time in the 1960s, I immediately knew exactly where Albinus’s wife and their little daughter were living. It was on the south side (right) of the street were the yellow elevated train dives underground, that is, on Kleiststrasse between Nollendorfplatz and Wittenbergplatz (the only other such place in the north of the city was excluded), and following Nabokov’s description of blind Albinus’s last taxi ride I arrived at exactly the house on Kaiserallee 56 (now Bundesallee) where Albinus and his mistress had stayed after his wife had left him. The house is still standing, rejuvenated.

I had long asked myself what was left of Nabokov’s Berlin. Very little, to be sure. He had lodged in ten apartment houses, including the two where his parents had lived. Six of them had been destroyed in the war, in two cases even the very street had vanished, and the four remaining ones had changed beyond recognition. The city block, as a matter the whole quarter where the daily Rul and the Slovo books were edited and published and where Nabokov had regularly gone to deliver his manuscripts to Yossif Gessen was obliterated, and so was the Police Headquarters were Russian émigrés regularly had to go to have their ID cards renewed and the Concert Hall where Nabokov’s father had been shot by two Russian assassins.

The Sportpalast, the Lunapark and the Wintergarten were no more, not even Potsdamer Platz and Friedrichstrasse were. The cafés and lecture halls where Russian writers had assembled had disappeared, and in some cases it even proved impossible to find out where they had been. The only place that was and is more or less the same is the sandy pine forest of Grunewald, though most of its butterflies are gone. It was the only place in Berlin Nabokov seems to have actually enjoyed, minus the aborigines and their junk.

As there was next to nothing left of Nabokov’s Berlin, I wondered if there were at least any photos of all those places. The situation was not very promising. Berlin has been amply photographed, but it was always the prominent sights, Potsdamer Platz, Friedrichstrasse, the Brandenburg Gate and so on, not the inconspicuous places that had caught Nabokov’s attention and turned up in his works. And many of the photos that there may have been have not survived the war and the division of the town. I had a list of some two hundred motives to look for. Some, I had thought, would be easy. There surely must be a man carrying pig halves into a butcher’s shop, the way I had seen it done as a very young child several times a week from my family's balcony, but no such photo seems to exist. There surely must be a photo from the twenties or thirties showing some standard back yard in the western part of the town, complete with an ambulant musician and a trestle to beat carpets. If I was lucky, I thought, I might even find one with a chessboard tiling like the one Luzhin let himself drop into. However, there just wasn’t, and I might have had better success if I had gone and looked for a surviving old courtyard in present day Berlin. Others I thought unlikely. For instance, I thought I would never find the photo of a dog catcher at the Hundekehle Lake or a truck with a complete larch-tree, and I did not. Instead, however, I found some that had seemed so unlikely that I had not even put them on my list, like the barber shop of Razor or the Museum of Crime in King, Queen, Knave. In the end, some one hundred close fits had turned up and any number of less close fits.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The cinema “Universum” on Kurfürstendamm, today “Schaubühne” |

|

|

|

|

|

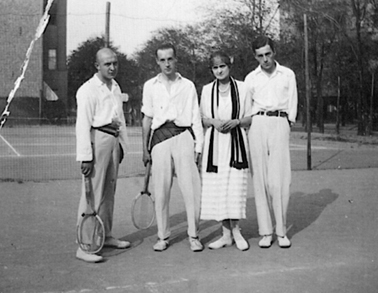

Nabokov (second from left) on the tennis court behind the “Universum” cinema

Squeezed in between apartment houses, the "Tennisplätze am Ku'Damm" where Nabokov used to play when he was living just two blocks away on Nestorstrasse are overdue to disappear, but they still existed in May, 2011.

Nestor- and Paulsborner Strasse today |

In a way, a search like this is a sport, and as such it is sometimes frustration and sometimes fun. In another way, it is a fight against oblivion. A really good find is like a victory over time.

One of the luckiest because most elusive finds was the building where Nabokov lived for five years, from 1932 to 1937, longer than in any other Berlin building. At first glance it seems to present no problem. You may go and look it up even today, Nestorstrasse 22 in Halensee (now part of the district of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf), near the far end of Kurfürstendamm.

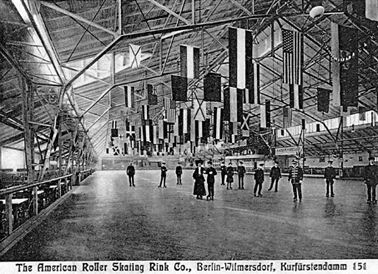

It is just behind the block where had been the Roller Skating Rink that had witnessed Nabokov’s first crush at the age of eleven. Later, he had given tennis lessons there. In the thirties, there was a big cinema (“Universum”) which finally was transformed into the theater (“Schaubühne”) where in 1996 Klaus Michael Grüber produced Nabokov’s play The Pole.

The building “Nestorstrasse 22” is standing or seems to be. Nabokovians have gone there and photographed it as I had done myself. It was in Daniela Rippl’s centenary exhibit and the ensuing book. Since 1999 there is a plate next to the front door commemorating Nabokov’s stay.

Yet I knew the present house couldn’t be it. In 1943 the whole corner building on Nestor- and Paulsborner Strasse had been destroyed by bombs down to the second floor. (Nabokov and Véra had lived on the third.) It had been rebuilt quite early, in 1952, which might account for the present drab and unprepossessing look. But had it been rebuilt as it was before?

Nestorstrasse figures prominently in The Gift where it is called “Agamemnon-strasse,” Fyodor’s third address in the course of the novel. How could I know? How could anybody know? It was not hard to identify. There is a would-be square close by, mockingly described by Fyodor, that gives it away:

“... there was a church, and a public garden, and a corner pharmacy, and a public convenience with thujas around it, and even a triangular island with a kiosk, at which tram conductors regaled themselves with milk. A multitude of streets diverging in all directions, jumping out from behind corners and skirting the above-mentioned places of prayer and refreshment, turned it all into one of those schematic pictures on which are depicted for the edification of beginning motorists all the elements of the city, all the possibilities for them to collide. To the right one saw the gates of a tram depot with three beautiful birches standing out against its cement background …” (The Gift, p.161)

There is only one square in Berlin where all these elements can be found in combination: an irregular intersection of various streets, a red brick church, a public garden (with a sandpit for children and an abandoned soccer field behind), a pissoir, a pharmacy, a tram depot. This is Hochmeisterplatz in Halensee, intersected by Nestorstrasse. As a matter of fact, “left” and “right” in the above description are as seen from Nestorstrasse 22.

So Nabokov had not invented Fyodor’s place of residence. He had not even placed him somewhere else in the city, as he easily might have done. He had simply lodged him exactly where he himself was living during the time of writing (but not in the mid-twenties when the novel is set), only changing Nestor into Agamemnon, one Greek king of the Trojan War into another. There is no Agamemnonstrasse in Berlin but a Hektorstrasse close by.

Identifying the locality so neatly, however, posed a problem. For according to the novel, Fyodor’s building should look like this:

|

|

|

Old map of Hochmeisterplatz in Halensee, with the streetcar depot on the lower right |

“The house in which Fyodor lived was a corner one and stuck out like a huge red ship, carrying a complex and glassy turreted structure on its bow, as if a dull, sedate architect had suddenly gone mad and made a sally into the sky. On all the little balconies which girdled the house in tier after tier there was something green blossoming, and only the Shchyogolevs’ was untidily empty, with an orphaned pot on the parapet and a corpse hung out in moth-eaten furs to air.” (The Gift, p.174)

The present building, however, is not at all ship-like and red, has no glassy turreted structure on its bow and no tiers of balconies. So had Nabokov invented Fyodor’s house? Had he borrowed it from elsewhere? Or did the old building differ that much from the present one?

That’s why it was imperative to find of photo of the building as it had been in the nineteen thirties. Bad luck. It was in none of the public and private archives were I asked and searched. There wasn’t even a decent picture of Hochmeisterplatz, except for an old one of the church and a very bad one of the tram depot. Then I learned there were aerial photos of most of Berlin from the late 1920s, and they still exist. On one of them I found the spot only to discover with dismay that in 1929 the building had been nothing but a construction site. They had another aerial photo from 1943. There the short-lived building was in ruins, the roof and the upper floors gone. From above, you could look right into the rooms Nabokov had rented until six years before.

I found out that miraculously the real estate and construction documents of the site were still preserved, and I applied in writing to be allowed to have a look into the folder. The present proprietors refused. As a last resort, I was going to place an ad in a local newspaper. Then one day I was turning the pages of a copious volume of local Wilmersdorf history looking for something else. Nestorstrasse 22 was in the back of my mind, but of course only in its present shape. That’s why at first I overlooked the photo. A few pages later suddenly an idea struck me, I turned the pages back—and there it was.

|

|

|

The corner of Nestor- and Paulsborner Strasse, aroundy 1931. According to The Gift, the striking color of the house was red. The Nabokovs entered from the door at the left. Their two rooms were on the third floor, looking out into a courtyard in the rear. They were the subtenants of Véra's cousin Anna Feigin, moving in on July 31, 1932. Nabokov left on January 18, 1937 for a lecture tour to Brussels, Paris and London, never to return. Véra and Dmitri followed him on May 6. |

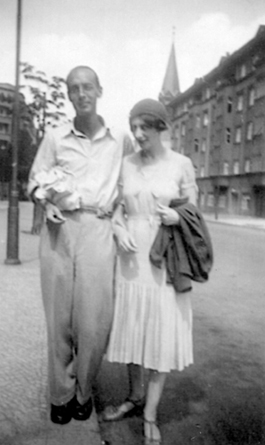

Everything fell into place. There are a few photos of Nabokov and his family taken somewhere in the vicinity. Now I could even pinpoint the spots on the sidewalk where they had been standing.

|

|

|

|

With Dmitri in front of the ship's bow |

On Nestorstrasse, in front of the entry door #22 |

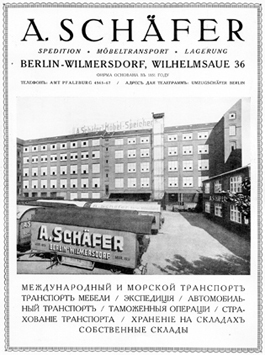

Here are a few quotes from The Gift and a few illustrations that correspond to them. The novel opens with a moving van waiting in front of the apartment house Fyodor is leaving.

|

|

“Running along [the van’s] entire side was the name of the moving company in yard-high blue letters, each of which (including a square dot) was shaded laterally with blue paint: a dishonest attempt to climb into the next dimension.” (The Gift, p.3)

The ad is from the opulent and glitzy Russian art magazine Zhar Ptitsa. The removal company Schäfer was obviously catering for the Russian community of Berlin. By coincidence, ten years later the company's head office was in the “Universum” cinema Nabokov was passing every time he walked from Nestorstrasse to Kurfürstendamm.

To quite appreciate the humor of the following quote, you have to be acquainted with Berlin. If you are, you will for instance notice that the little boy unknowingly is quite right when he calls the street they are passing at that moment “President Street,” for it is Wilhelmstrasse:

|

|

|

A restaurant on Potsdamer Platz |

|

|

|

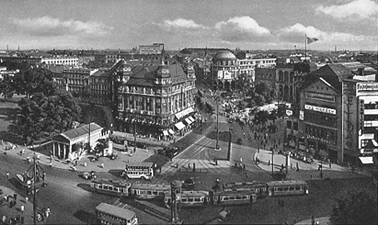

Potsdamer Platz |

|

|

|

Brandenburg Gate |

|

|

|

Unter den Linden - The large building on the right hand is the Staatsbibliothek frequented by Nabokov |

|

|

|

|

|

The Funkturm (Radio Tower) built 1925 for the Radio Exhibition in Berlin's old Messestadt |

|

|

|

One of the exhibition halls of the Museum of Crime |

|

|

|

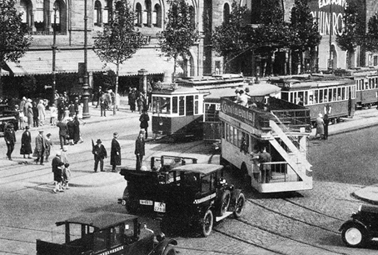

An open-decked bus, streetcars and taxi cabs near the Zoo |

“As [Martin Edelweiss] sat in the bus he heard a ripple of Muscovite speech near him. It came from a couple, of Soviet rather than émigré aspect, and their roundeyed little boys. The elder had settled close to the window, the younger kept pressing against his brother. ‘A restaurant,’ the bigger said ecstatically. ‘Look, a restaurant!’ said the smaller one, pressing. ‘I can see for myself,’ snapped his brother. ‘It’s a restaurant,’ said the smaller one with conviction. ‘Shut up, idiot,’ said his brother. ‘It’s not the Linden yet, is it?’ the mother asked worriedly. ‘It’s still the Post Dammer,’ said the father with authority. ‘We’ve already passed the Post Dammer,’ cried the boys, and there ensued a short argument. ‘What an archway, that’s class for you,’ exulted the elder boy stabbing at the window with his finger. ‘Don’t yell like that,’ remarked the father. ‘What’s that?’ ‘I said don’t yell.’ The boy looked hurt. ‘In the first place I spoke softly, and did not yell at all.’ ‘Archway,’ uttered the smaller boy with awe. The whole family became absorbed in the contemplation of the Brandenburg Gate. ‘Historical site,’ the bigger boy said. ‘An ancient arch, yes,’ confirmed the father. ‘How shall we wriggle through?’ the bigger boy wondered, fearing for the sides of the bus, ‘it’s a squeeze!’ ‘We did wriggle through,’ the smaller boy whispered with relief. ‘And now this is the Unter,’ cried the mother, ‘time to get off.’ ‘The Unter is such a long, long street,’ said the bigger boy, ‘I saw it on the map.’ ‘This is President Street,’ said the smaller boy dreamily. ‘Shut up, idiot! It’s the Unter Linden.’ Then, in chorus, ‘Unter is long, long, long,’ and a male solo voice, ‘It’s an endless journey.’” (Glory, p.183-4)

The old Radio Tower built in 1925 has been reduced to a marginal existence and its revolving searchlight has not returned after WW2, but here it keeps skimming the roofs:

“It was a black and boisterous night; every five seconds there would come, skimming across the roofs, the pale beam of the Radio Tower: a luminous twitch; the wild lunacy of a revolving searchlight.” (Despair, p.64)

The Museum of Crime of King, Queen, Knave actually did exist. It was not lodged at the Courthouse in Moabit but right at the Police Headquarters on Alexanderplatz where foreigners had to report once every six months to have their ID cards stamped. No doubt Nabokov had inspected it at one such occasion.

“In an annex to the courthouse, the police had staged an exhibition of crime. […] Dreyer […] strolled through all the rooms. He examined the faces of criminals, enlarged photographs of ears, messy fingerprints, kitchen knives, ropes, faded shreds of clothing, dusty jars, dirty test tubes—a thousand trivial articles that had been wronged—and again rows of photographs, the pasty faces of unwashed, badly dressed murderers, and the puffy faces of their victims who in death came to resemble them; and it was all so shabby, so stupid, that Dreyer could not help smiling. He was thinking what a talentless person one must be, what a poor thinker or hysterical fool, to murder one’s neighbor. The deathly gray of the exhibits, the banality of crime, pieces of bourgeois furniture, a frightened little console on which a bloody imprint had been found, hazel nuts injected with strychnine, buttons, a tin basin, again photographs—all this trash expressed the very essence of crime.” (King, Queen, Knave, p.206-7)

Up to the early 1930s, there were open-decked buses on the streets of Berlin. Franz, being extremely near-sighted and unused to city traffic, was befuddled by them.

“Almost directly the yellow mirage of a bus came into being. Stepping on somebody’s foot, which at once dissolved under him as everything else was dissolving, Franz seized the handrail and a voice—evidently the conductor’s—barked in his ear: “Up!” […] When the bus jerked into motion he caught a frightening glimpse of the asphalt rising like a silvery wall, grabbed someone’s shoulder, and carried along by the force of an inexorable curve, during which the whole bus seemed to heel over, zoomed up the last steps and found himself on top. He sat down and looked around with helpless indignation. He was floating very high above the city. […] The clean air whistled in his ears, and the horns called to each other in celestial voices.” (King, Queen, Knave, p.24)

Did anybody celebrate the play of night lights on wet asphalt as painstakingly and enthusiastically as did Nabokov? “The lustre of the black asphalt was filmed by a blend of dim hues, through which here and there vivid rends and oval holes made by rain puddles revealed the authentic colors of deep reflections—a vermilion diagonal band, a cobalt wedge, a green spiral—scattered glimpses into a humid upside-down world, into a dizzy geometry of gems.” (King, Queen, Knave, p.74)

|

|

|

City lights on Nollendorfplatz |

Works Cited

Nabokov, Vladimir. Despair. Trans. by Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Vintage International, 1989.

The Gift. Trans. by Michael Scammell and Dmitri Nabokov with Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Vintage International, 1991.

Glory. Trans. by Dmitri Nabokov with Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Vintage International, 1991.

King, Queen, Knave. Trans. by Dmitri Nabokov with Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Vintage International, 1989.

Zimmer, Dieter E. Nabokovs Berlin. Berlin: Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, 2001. 155 pp., c. 160 ill., EUR 24,90. ISBN 3-87584-095-X